Use these tips to determine what will work best for your school community.

To ban or not to ban? That's the question that schools have been asking since cellphones were invented. But recently the conversation has reached a peak, with state bills being passed that dictate what some districts should do.

Meanwhile, teachers are navigating classrooms in which students are creating TikToks, scrolling, and gaming—while they should be paying attention. In our research, 53% of tweens (age 8–12) and 69% of teens (age 13–18) reported that using social media distracts them when they should be doing schoolwork. To many, school phone bans seem like a no-brainer. Yet the question of establishing and enforcing bans isn't always a simple one.

For some communities, a full ban is totally achievable. But, for example, in a high school of 3,000 students, having the resources to secure every student's phone but also allow access with varied schedules and needs and still address parent concerns around safety is nearly impossible. A legislative ban won't account for these challenges, which then fall to administrators and educators to overcome.

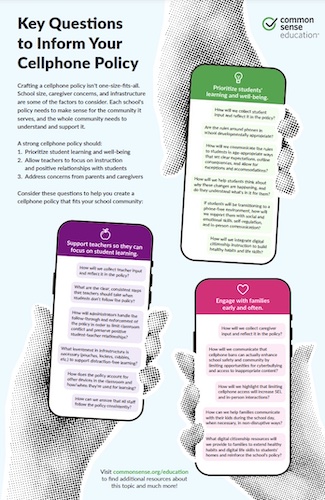

Ultimately, a school's phone policy needs to make sense for the community it serves, and the school needs the support to enforce it. Here are our recommendations to determine what will work for your community—and how to make it happen:

Involve the community

If all stakeholders are involved in the creation and implementation of the policy, there will be more buy-in and support. Allow input from families, educators, and students themselves in as many accessible ways as you can handle: in person, via survey, during set "office hours," etc. There's never total agreement, but hearing from as many affected parties as possible is critical to success.

Then, it's important to communicate the steps in the creation process to those who didn't participate. You can even make it an exciting "reboot" to make sure it doesn't fly under the radar. Ultimately, listen carefully, and then communicate widely.

Prioritize and set realistic goals

Once you've gathered information and gotten input, it's time to prioritize. With learning, connection, safety, and a positive school culture at the forefront (for example), how do personal devices fit into those priorities? Are violence and classroom management big concerns at your school? What about equity?

Bottom line: If teachers are left to enforce device policies without consistent recourse, they're being given an impossible task.

For instance, in that high school of 3,000 mentioned earlier, stakeholders might decide that 1) cellphones are a distraction in class, but 2) some students need their phones for jobs or transit, so then 3) allowing phones on campus but not in the classrooms might be feasible if everyone works together to enforce the policy.

Bottom line: If teachers are left to enforce device policies without consistent recourse, they're being given an impossible task. Similarly, if the majority of families object to the school's enforcement of the policy, it won't work. You'll likely encounter obstacles, but if the process of creation is sound, the communications are clear, and the enforcement is consistent, over time the results will likely speak for themselves.

Consider research and developmentally appropriate practices

Use existing research about general school cellphone use and any localized data you can gather to serve as a foundation for change. Research about cellphone use and its impacts or recommendations from respected institutions are a good place to start. Along these lines, it's crucial to consider the ages and needs of the students in your school(s), as the ability of elementary school students to self-regulate differs from teens.

Perhaps most essentially, the students themselves have to learn how to manage personal devices and their use.

Make digital citizenship core to student culture

Perhaps most essentially, the students themselves have to learn how to manage personal devices and their use. If we're honest with ourselves, we know that many adults struggle with how distracting and compulsive cellphone use can be. Our students developmentally have fewer self-regulation skills than we do, so if we want to see change in how students relate to their devices, we need to be one piece of the larger puzzle making that happen.

Creating a culture of digital citizenship means infusing it into daily school life and giving strategies to families for use at home. And while digital citizenship is sometimes seen as internet safety and anti-cyberbullying programs, there's so much more to helping students understand the whole constellation of concepts that come with device use. Helping kids reflect on why they pick up their phones, why it's hard to put them down, and how their device use affects them are just a handful of other key elements that lead to stronger self-regulation skills. This also includes modeling, so while adults in schools may have lots of valid reasons to check their own phones, "walking the walk" is also really important.

We have a ton of free student- and teacher-facing resources that fit just about every use case, and we're always working to create more and get them in your hands. We're also engaging with lawmakers and families, because we all (not just schools and teachers) need to work together to support kids' well-being. So whether you decide to ban, not ban, or something in between, taking a whole-community approach—with digital citizenship at the core—is a powerful way forward.

Resources:

Cellphone Policies

- Creating a Cellphone Policy That Works for Everyone

- Screen Time in School: Finding the Right Balance for Your Classroom

- Practical Tips to Handle Cellphones in Schools

Infusing Digital Citizenship

- Digital Citizenship Curriculum

- Digital Citizenship Lesson Collections (AI literacy, digital well-being, device advice, and more!)

- Here's Why One Week of Digital Citizenship Isn't Enough

- 5 Easy Ways to Integrate Digital Citizenship Every Day

- Digital Citizenship: Establish Trust with Transparency

- Use "Accountabilibuddies" to Approach Digital Citizenship

- How to Get Buy-In to Boost Digital Citizenship

- Offline Digital Citizenship: Soft Skills to Support Strong Online Habits

- Taking a Stand on Cellphone Bans

Involving the Community

- Family and Community Engagement Program (FACE)

- How to Get on the Same Page as Parents and Caregivers

- Family Engagement Toolkit

- Family Tech Planners